Freediving is not a leisure activity; it is a sport that requires a great deal of skill. These skills include both the obvious, “visible skills” and the less obvious, “invisible skills.” The latter are revealed and amplified by the ocean’s unique environment, making them even a decisive factor.

If you don’t meet certain technical requirements, you simply can’t get started. Right now, I find myself pacing back and forth at this threshold, hesitant and unsure if I will ever be able to step through that door.

Next, I will share my experience in detail.

This is Her

Dahab isn’t exactly a tourist hotspot. People who come here either have a clear purpose or have been persuaded to come—there’s almost no middle ground. The rule here is that almost every activity has a certain threshold. In other words, if you want to take part in something interesting, you either need exceptional talent, special courage and energy, or well-honed skills. There are almost no activities that can be experienced effortlessly, like visiting a scenic spot or museum, which only requires walking.

After spending a few days here, I deeply felt that Dahab is not flattering at all. It generously showcases the Blue Hole, cliffs, and lagoons. If you want to play, you can come; whether you have the ability or not is your own business, not its. It won’t lower the bar or make things easier just so you can have fun. This proactive attitude is unique among tourist destinations—you either throw yourself into the cliffs and ocean or lie in the shade complaining. So my advice is to use your imagination fully before coming and be clear about which sports you want to try, to avoid boredom.

Fish

I signed up for a freediving experience course, which is level one in the AIDA system. Simply put, diving falls into two main categories: one is what we usually call “diving,” which involves going underwater with oxygen tanks; the other is going underwater without any equipment, relying solely on your body—that’s the meaning of “free” in freediving. The former is better known through the PADI system, while the latter includes the AIDA or Molchanovs systems. These names aren’t that important—you can find plenty of information with a quick search. Although I joined the system and the course has levels, I know very well that this doesn’t represent my personal ability; it’s just proof that I’ve been there. I have no special expectations and do not wish to overly promote the so-called certificate.

Because it was windy and the water surface was rough that day, we split the course into two days: half a day of theory and half a day of practice. The coach lives on the town’s north road, about a ten-minute walk from where I was staying. Without a house number, I just roughly followed the Weixin location. When I arrived, I looked around but couldn’t tell what was ruins and what was a residence; all I saw was a cluster of yellow-flowered trees casting shadows and smelled a strong scent of sheep dung.

The coach saw I had arrived and came down to open the door for me. I went up the stairs and entered the house with him. The interior was simple, like old houses in China, very functional. There was a carpet on the floor, and next to it were various diving gear and teaching aids. Although I couldn’t name them, they looked very professional. Since it was a beginner course, the content was straightforward and mostly introductory. The focus was on safety first, then technique. After the course, I chatted with the coach for a while before leaving.

The course mentioned that freediving is a “mental game.” This phrase stuck with me. Generally, a game is a broad concept that applies to most activities. It tests various abilities like endurance, skill, flexibility, memory, and so on. I tend to associate different abilities with certain activities—for example, memory is like a bespectacled scholar, flexibility like a tall, lean athlete, the latter being a manifestation of the former. As for what a person with strong mental ability looks like, or how mental strength manifests, I can’t say for sure. That’s why I’m curious to “play this game” myself and experience the strength of the mind firsthand.

Another thing that impressed me was the “buddy system”, meaning freediving is always done with at least two people to ensure safety. So freediving demands not only individual mental strength but also connection between people. These two combined are like the elements of creation—one inward, one outward—and only when inside and outside unite is it complete. Two people, life, and the ocean: many elements naturally and harmoniously merge in freediving.

On the way back, I kept reflecting on these fascinating ideas. Of course, theory is theory, and in the end, it all comes down to practice.

Fish and coral

A few days later, the wind died down. We chose a sunny morning for my first dive.

There’s a lighthouse on the south side of town, the busiest spot around. Thanks to its unique geography, it’s the best place to dive. The shallow waters nearby are perfect for snorkeling, while farther out you can do scuba or freediving.

We found a café, and the coach brought out a buoy from the backyard. I learned that when he teaches others, he either partners with a dive shop or works independently. He just needs to notify the café in advance, store his gear there temporarily, and order some food and drinks during classes—a mutually beneficial arrangement.

I first put on a wetsuit. It felt like synthetic fiber, thick and soft to the touch, as if insulated inside. Wearing a wetsuit means covering your entire body, head to toe. Even with long sun exposure, the seawater remains cold, and if you’re not properly covered, you risk hypothermia. Also, because seawater is buoyant, you need to wear extra weights to sink. Finally, I put on the mask and snorkel, grabbed the long fins, and was ready to go. Freediving gear is quite a bit, but much lighter than scuba gear, which sometimes requires a cart to carry.

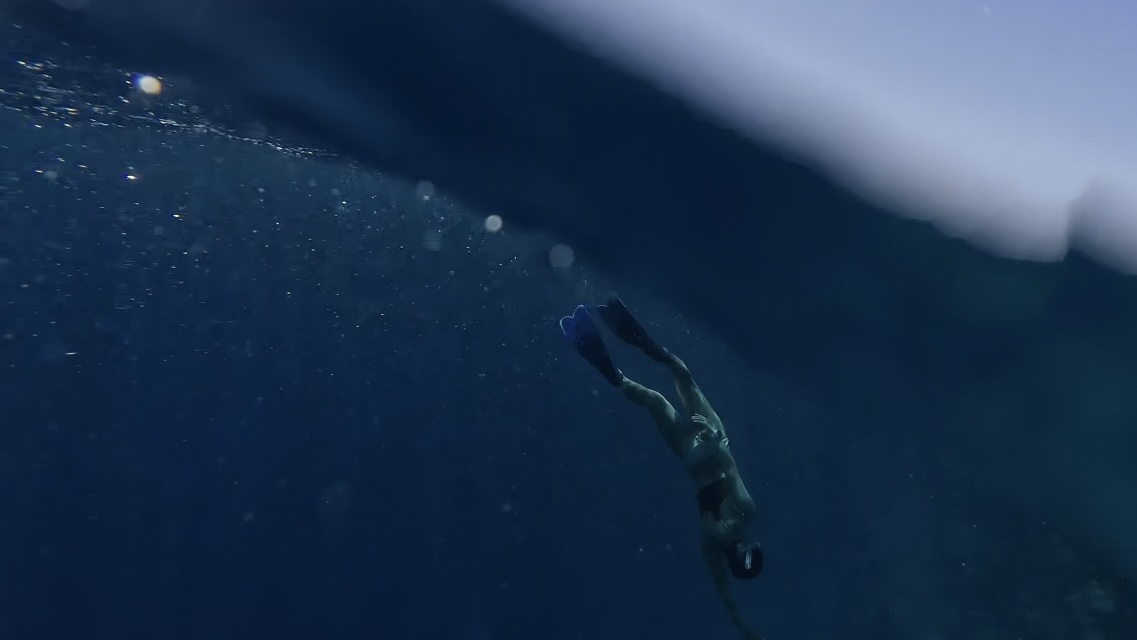

Once in the water, the shallow beach was very shallow—I remember the water only reached my thighs. The coach guided me through some simple moves like spitting out water, lying down to relax, and how to use the fins. The most interesting part was breathing relaxation: lying on the surface, scanning my body, relaxing, and then holding my breath at the most relaxed moment. My body was buoyed by the water, floating motionless, with only my brain seemingly active. Thoughts surged—sometimes colorful and flying, sometimes silent and empty, leaving only pure sensation. My body was suspended between sky and sea, as thin as a cicada’s wing, melting at the boundary and drifting with the waves.

People use various methods to calm their racing nerves; the textbook suggests imagining a burning candle. Some imagine animals, others plants. I lacked experience and had no method, even resorting to reciting the “Heart Sutra” to calm myself, but it didn’t work well because I forgot the words, which annoyed me and made me more unstable. In the end, I held my breath for one and a half minutes, an average result. Compared to professionals who can hold their breath for several minutes, the gap was clear.

After the basic training, we moved to a slightly deeper spot, about seven or eight meters deep. The water was clear, and I could see the seabed. After the coach secured the buoy, I tried to dive.

I inverted myself, held the rope, and gently pulled down. The pressure in my ears changed suddenly, followed by pain. The pain started broad and then sharpened. Every time I dived, I tried to equalize the pressure, but no matter how well I trained on land, it failed immediately underwater. Even when calm and carefully focusing on my throat, vocal cords, pharynx, and facial muscles, the sensation became confused as waves passed. The seawater pressure came from all directions, tight and unyielding, seeping into every possible gap. The deeper I went, the tighter the pressure and the greater the pain. The pressure was inevitable, like causality; facing it, there was no choice but to use the correct technique. That feeling of helplessness was magnified underwater; either you do it poorly or you can’t do it at all, with no solution. I had no complaints but quickly surfaced after only one or two meters.

I tried several times to invert and dive but failed each time. A yellow tennis ball hanging at five meters glowed like a mirage, beckoning me, but sadly I couldn’t meet its call. Water pressure and technique were the barriers.

After spending over an hour in the sea, my body started to get cold, so I told the coach we could stop. Back on shore, the sun was strong, but my body still trembled involuntarily. Reflecting on the dive, most of my feelings were excitement about the new experience, but part of me was frustrated, like I had missed the final step. Though imperfect, I could accept it and wasn’t ready to give up diving. The good news is that by the time I’m writing this, I’ve mastered the ear equalizing technique but still need to practice and adjust underwater.

More fish and coral

Later, I talked about this experience with my girlfriend. She said the coach commented on our training spot’s distance from shore, calling the location and depth very “magical” and “subtle.”

I completely agree and empathize. People who don’t dive stay close to shore; those eager to start go farther out. I’m somewhere in between—not quite a beginner, but not a non-diver either. This perfectly describes my conflicted hesitation on the path to learning diving.

Freediving itself seems inherently contradictory. Successful diving requires performing specific actions while maintaining total relaxation. Most of the time, these two contradict each other: actions tense the muscles, while relaxation resists tension and halts movement. This contradiction is fully triggered in this special environment. I believe every skilled freediver is a master of balance. They know how to find equilibrium between tension and relaxation, moving fluidly like a fish in the space between motion and stillness, pursuing the greatest depth and the deepest self.